Writing

Macros

This

lecture will focus on writing macros,

and use stack handling

as an example of macro use.

Macros

differ from standard subroutines and functions.

Functions

and subroutines represent separate blocks of code to which

control can be transferred. Linkage is

achieved by management of

a return address, which is managed

in various ways.

A

macro represents code that is automatically generated by the assembler

and inserted into the source code.

Macros

are less efficient in terms of code space; each invocation

of the macro will generate a copy of the code.

Macros

are more efficient in terms of run time;

they lack the overhead associated with subroutine call and return.

Before

discussing macros, let’s discuss an application.

Dynamic

Memory: Stacks and Heaps

The

first thing we note is that the IBM 370 supports neither in native mode.

A

stack is a LIFO (Last–In /

First–Out) data structure with three basic

operations: PUSH places

an item onto the stack,

POP removes an item from the stack

INIT initializes the stack.

A heap is a dynamic structure

used by a RTS (Run–Time System) to allocate

memory in response to object creators, such as New.

A

modern RTS will allocate an area of memory for use by both the stack and

the heap. By convention in system design:

The

stack starts at high memory addresses and moves toward lower addresses.

The

heap starts at low memory addresses and moves toward higher addresses.

NOTE:

IBM has macros called “PUSH” and “POP”, associated with handling

print output. We must pick other names

for our stack macros.

Division of

the Dynamic Memory Space

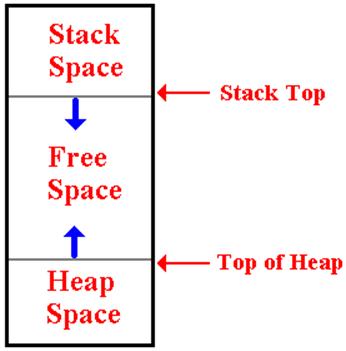

This

shows how the available space is divided between the stack and the heap.

There

is no fixed allocation to either, just a limit on the total space used.

A

stack is often managed using a stack pointer, SP, that

locates its top.

Our Stack

Implementation

Our

goal in this lecture is to examine the basic stack structure,

and its implementation using macros.

Our

implementation will use a fixed–size array to hold the stack.

The stack will grow towards higher addresses.

The

stack pointer will point to the location into which the

next item will be pushed.

PUSH

STACK[SP] = ITEM

STACK[SP] = ITEM

SP = SP + 1 // Moves toward higher addresses

POP

SP = SP –

1

SP = SP –

1

ITEM = STACK[SP]

This

non–standard approach is easier for me to code.

A Stack

Example

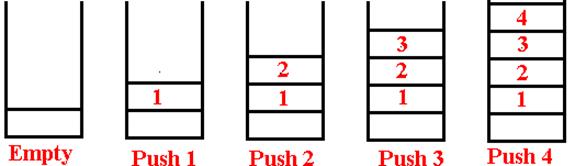

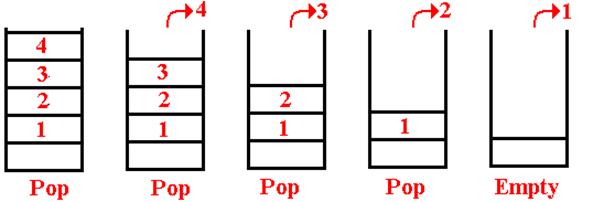

Here

we push four integers, one after the other.

We then pop the values.

Push

onto the stack

Pop

from the stack: note the order is reversed.

Our Stack

Implementation: Macro or Subroutine?

We

have a choice of implementation method to use for our stack handler.

I

have chosen to use an approach using macros for two reasons.

1. I

wanted to discuss macros.

2. I

wanted to use a stack to illustrate the subroutine call mechanism.

That makes it difficult to

use a subroutine for the stack.

We

shall write three macros for the stack.

STKINIT This is a macro without parameters.

It will initialize the

stack count; hence, the stack pointer.

STKPUSH This is a macro with a single parameter.

It pushes the 32–bit contents

of a register onto the stack.

STKPOP This is a macro with a single parameter.

It pops the contents of the

stack top into a 32–bit register.

AGAIN: These names are chosen to avoid name

conflicts with existing macros.

Mechanics of

Writing Macros

The

MACRO definitions should occur very early in the program text.

Only

comments and assembler control directives may precede a

MACRO definition. This commonly includes

the PRINT directive.

A

MACRO begins with the key word MACRO, includes a prototype and

a macro body, and ends with the trailer keyword MEND.

Parameters

to a MACRO are prefixed by the ampersand “&”.

Here

is an example.

Header MACRO

Prototype DIVID ",&DIVIDEND,&DIVISOR

Model

Statements ZAP &QOUT,&DIVIDEND

DP ",&DIVISOR

Trailer MEND

Note

that the header and trailer must appear as is.

Each of the terms “MACRO”

and “MEND”

begin in column 10. Nothing else is

allowed on either line.

Example of

Macro Expansion

In

assembly language, a macro is a single statement that causes the assembler

to emit a sequence of other statements specified by the macro definition.

Consider

the above example, with prototype

DIVID ",&DIVIDEND,&DIVISOR.

The

macro body is

ZAP &QOUT,&DIVIDEND

DP ",&DIVISOR

Here

is an example of the macro expansion. We

assume that the labels

used as “parameters” have been properly defined by DS or DC statements.

DIVID

MPG,MILES,GALS

MACRO INSTRUCTION

+ ZAP

MPG,MILES

ITS EXPANSION

+ DP

MPG,GALS

Symbolic

Parameters

The

macro prototype contains a list of symbolic parameters.

Each

symbolic parameter is written as follows:

1. The

name begins with an ampersand (&).

2. The

ampersand is followed by one to seven alphanumeric

characters, the first of

which must be a letter.

3. Put

another way, the first character of the name must be a “&”

and the second character of

the name must be a letter.

Note

that this “seven character” rule limits the total length of the symbolic

parameter to eight characters: the “&” and the 1 – 7 others.

According

to the IBM HLASM reference manual, “Symbolic parameters

have a local scope; that is, the name and value they are assigned only applies

to the macro definition in which they have been declared”.

Page

251, High Level Assembler for z/OS &

z/VM & z/VSE Language

Reference Manual,

Release 6 (July 2008), SC26–4940–05

A

Potential Problem with Macros.

It

might appear that a macro invocation cannot be the target of a branch

instruction. Here is some of my early

code.

I

had defined a macro, STKPOP, in the proper place.

It was used by

a routine, called DOFACT, to be discussed later.

I

tried the following code:

B DOFACT CALL THE FACTORIAL CODE

Here

is the branch target.

DOFACT STKPOP 4 POP THE ARGUMENT

INTO R4

STKPOP 8 POP THE RETURN ADDRESS

BR 8 BRANCH TO RETURN ADDRESS

That

did not assemble. The complaint was that

the symbol DOFACT was not

defined. What happened? The label was clearly there in the source

code.

Here is What Happened.

Consider

the following expansion from a macro call.

It has been edited for clarity.

0000BA 4840 C4AE 134 A92POP LH 4,STKCOUNT

0000BE 4940 C5B4 135 CH 4,=H'0'

0000C2 47D0 C0FE 136 BNP A98DONE

137

STKPOP 4

0000C6 4830 C4AE 138+ LH 3,STKCOUNT

0000CA 4B30 C5B2 139+ SH

3,=H'1'

0000CE 4030 C4AE 140+ STH 3,STKCOUNT

0000D2 8B30 0002 141+

0000D6 4120 C4B2 142+

LA 2,THESTACK

0000DA 5843 2000 143+ L

4,0(3,2)

0000DE The next

instruction

Note that the STKPOP

instruction on line 137 is not assigned an address.

The instruction on line 136

is at address C2 and has length 4. The next instruction

will be at address C6. Only the expanded

code is “real”.

In other words, we note two

facts:

1. The expansion

code is what counts for code accuracy.

2. The label DOFACT

does not “make it” into the expanded code.

The Solution

to the Branch Target Problem

In

order to solve the above problem, we need to focus on a more precise statement

of the form of a macro definition. We

must focus on the prototype and body.

The

general form of a prototype statement is as follows.

Symbolic Name Name of macro Zero or

more symbolic parameters

If

the symbolic name is to be used, it has the form of a symbolic parameter.

If

the symbolic name is to be used, it must be duplicated on the first line of the

body.

Here

is an example, using the DIVID macro.

MACRO

&LABEL DIVID ",&DIVIDEND,&DIVISOR

&LABEL ZAP &QOUT,&DIVIDEND

DP ",&DIVISOR

MEND

Note

that the symbolic parameter “&LABEL” is treated as any other such parameter.

Code Example

to Illustrate the Solution

MACRO

&LABEL DIVID ",&DIVIDEND,&DIVISOR

&LABEL ZAP &QOUT,&DIVIDEND

DP ",&DIVISOR

MEND

B10DIV DIVID X,Y,Z

+B10DIV ZAP

X,Y

DP

X,Z

B20DIV

DIVID A,B,C

+B20DIV ZAP

A,B

DP

A,C

Note

that each of the labels B10DIV and B20DIV now appears in the expanded code

and can be used as a branch target address.

Concatenation:

Building Operations

In

a model statement, it is possible to concatenate two strings of characters.

Consider

the macro prototype to load a register from one of several sources.

Note the use of the string “&NAME” to allow this to be a branch target.

MACRO

&NAME LOAD ®,&TYPE,&ARG

&NAME L&TYPE ®,&ARG

MEND

Consider

a number of invocations.

LOAD R7,R,R6 becomes LR R7,R6

LOAD R7,H,HW becomes LH R7,HW

LOAD R7,,FW becomes L R7,FW

Note

here: the second argument is empty. The

empty string is concatenated to “F”.

As soon as I can verify a few

particulars, I shall extend the stack operations to

push and pop contents of half–words and full–words.

Our Stack

Data Structure

The

stack is implemented as an array of full words, with two

auxiliary counters.

There

is a halfword that counts the number of items on the stack.

There

is a halfword constant that gives the maximum stack capacity.

This is not changed by the code.

There

is the fixed–size array that holds the stack elements.

Here

is the declaration of the stack.

STKCOUNT DC H’0’

NUMBER OF ITEMS STORED ON STACK

STKSIZE DC H’64’ MAXIMUM STACK CAPACITY

THESTACK DC 64F’0’ THE STACK HOLDS 64 FULLWORDS

Note that the elements

are full–words while the addresses are byte addresses.

The elements of the

stack will be stored at the following addresses.

THESTACK, THESTACK + 4,

THESTACK + 8, THESTACK + 12

up to a full word starting at THESTACK + 252.

Initialize

the Stack

Here

is the macro that initializes the stack.

*STKINIT

MACRO

&L1

STKINIT

&L1 SR 4,4 CLEAR R4 – SUBTRACT FROM SELF

STH 4,STKCOUNT STORE AS

THE STACK COUNT

MEND

*

Note the standard trick

of clearing a register by subtracting it from itself.

The register exists only

for the purpose of placing a 0 into the stack count.

Following standard

practice, the contents of the stack are not changed,

because the elements of interest will be overwritten before they are used.

Note that this macro

does not have any symbolic parameters.

PUSH:

Placing Items Onto the Stack

Here is the macro

STKPUSH

*STKPUSH

MACRO

&L2 STKPUSH &R

&L2 LH 3,STKCOUNT GET THE CURRENT STACK SIZE

*

LA 2,THESTACK GET ADDRESS OF STACK START

ST &R,0(3,2) STORE THE ITEM INTO THE STACK

LH 3,STKCOUNT GET THE (NOW) OLD STACK SIZE

AH 3,=H’1’ INCREASE THE SIZE BY ONE

STH 3,STKCOUNT STORE THE

NEW SIZE

MEND

*

This

macro has one symbolic parameter: &R. It is to be a

register number.

When

called as STKPUSH 4, the operative statement is changed by the

assembler to ST 4,0(3,2) and executed as

such at run time.

POP:

Removing Items From the Stack

Here

is the macro STKPOP

*STKPOP

MACRO

&L3

STKPOP &R

&L3 LH 3,STKCOUNT GET THE STACK COUNT

SH 3,=H’1’ SUBTRACT 1 WORD OFFSET OF TOP

STH 3,STKCOUNT STORE AS

NEW SIZE

LA 2,THESTACK ADDRESS OF STACK BASE

L &R,0(3,2) LOAD ITEM INTO THE REGISTER

MEND

*

Again,

this macro has one symbolic parameter: &R. Again, a register number.

When

called as STKPOP 6, this is assembled with the last statement as

L 6,0(3,2).

NOTE: When invoked as STKPOP MYDOG, this

will

assemble as L MYDOG,0(3,2); the

assembler takes anything.

Using the

Macros

Here

is the part of the unexpanded source code that uses the macros.

STARTUP OPEN

(FILEIN,(INPUT)) OPEN THE STANDARD

INPUT

OPEN

(PRINTER,(OUTPUT)) OPEN THE STANDARD OUTPUT

PUT

PRINTER,PRHEAD

PRINT HEADER

STKINIT INITIALIZE

THE STACK

GET

FILEIN,RECORDIN

GET THE FIRST RECORD, IF THERE

*

* READ AND PROCESS

*

A10LOOP MVC

DATAPR,RECORDIN MOVE INPUT

RECORD

PUT

PRINTER,PRINT

PRINT THE RECORD

PACK

PACKIN,FIELD01

CONVERT DIGITS INPUT TO PACKED

CVB R4,PACKIN

CONVERT THE NUMBER TO BINARY

STKPUSH 4 PUSH THE

NUMBER ONTO THE STACK

GET

FILEIN,RECORDIN

GET THE NEXT RECORD

B

A10LOOP GO BACK AND PROCESS

*

Here,

it is obvious that I have retained register R4 for communicating results

with macros and subroutines. That is an

arbitrary choice.

Using the

Macros (Page 2)

Here

is the unexpanded source code that uses the stack pop.

* END OF INPUT

PROCESSING

*

A90END CLOSE

FILEIN

PUT

PRINTER,ENDNOTE

ANNOUNCE THE END OF INPUT DATA

A92POP LH 4,STKCOUNT GET THE STACK COUNT

CH 4,=H’0’ IS THE COUNT POSITIVE?

BNP

A98DONE NO, WE ARE DONE

STKPOP 4 GET NEXT

NUMBER INTO R4

MVC

PRINT,BLANKS

CLEAR THE OUTPUT BUFFER

BAL 8,NUMOUT

PRODUCE THE FORMATTED SUM

MVC

DATAPR,THENUM

AND COPY TO THE PRINT AREA

PUT

PRINTER,PRINT

PRINT THE RESULT

B A92POP GO AND GET ANOTHER OUTPUT

A98DONE CLOSE

PRINTER

Expansion of

the Stack Pop

Here

is the expanded code, edited from the assembler listing.

136 A92POP LH 4,STKCOUNT

137 CH 4,=H'0'

138 BNP A98DONE

139 STKPOP 4

140+ LH 3,STKCOUNT

141+ CH 3,=H'0'

142+ SH 3,=H'1'

143+ STH 3,STKCOUNT

144+

145+ LA 2,THESTACK

146+ L

4,0(3,2)

147 MVC PRINT,BLANKS

148 BAL 8,NUMOUT

149 MVC DATAPR,THENUM

150 PUT PRINTER,PRINT

151 *

Note: There is no RETURN statement or the like.

The code is inserted in line.

A Problem

with the Macros

There

is a problem with each of the macros STKPUSH and STKPOP.

We

show it for STKPOP, because it is easier to see in this macro.

Suppose

we have code with the following two macro calls,

one immediately following the other.

STKINIT

STKPOP 6 NOTE:

WE HAVE NOT PUSHED AN ITEM

The

macro STKINIT will set the value at location STKCOUNT to 0.

Now

look at the code in the expansion of macro STKPOP.

139 STKPOP 4

140+ LH 3,STKCOUNT

141+ CH 3,=H'0'

142+ SH 3,=H'1'

143+ STH 3,STKCOUNT

STKCOUNT will be set to –1, and

the pop will reference the full word just

before the stack. This is the pair

STKCOUNT, STKSIZE: an error.

Avoiding the

Problem: A Flawed Solution

The

obvious solution is to test the value of STKCOUNT and avoid

popping a value if the stack is empty.

Here

is some code that appears to do just that.

*STKPOP

MACRO

STKPOP &R

LH 3,STKCOUNT GET THE STACK SIZE

CH 3,=H'0'

BNP NOPOP

SH 3,=H'1' SUBTRACT 1 WORD OFFSET OF LAST

STH 3,STKCOUNT WORD AND STORE AS NEW SIZE

LA 2,THESTACK ADDRESS OF STACK START

L

&R,0(3,2) LOAD ITEM INTO R4

NOPOP NOP A DO NOTHING TARGET FOR BNP

MEND

*

If

the macro is written this way, the code will assemble and run correctly.

What Is the Flaw?

The macro definition given above works ONLY because

the macro is

invoked only one time. If the macro is invoked twice, trouble

appears.

In

this modification of running code, the macro is called twice in a row.

A90END CLOSE FILEIN NO MORE INPUT TO PROCESS

PUT PRINTER,ENDNOTE NOTE THE END OF DATA INPUT

A92POP LH 4,STKCOUNT GET THE STACK COUNT

CH 4,=H'0' IS IT POSITIVE

BNP A98DONE NO - WE ARE DONE HERE

STKPOP 4 GET NEXT NUMBER INTO R4

STKPOP 5 **** BAD CALL

MVC PRINT,BLANKS CLEAR THE OUTPUT AREA

BAL 8,NUMOUT PRODUCE THE FORMATTED SUM

MVC DATAPR,THENUM AND MOVE TO PRINT AREA

PUT PRINTER,PRINT PRINT THE NUMBER

B

A92POP GO GET

ANOTHER

A98DONE CLOSE PRINTER

Listing for

Double Use of the Macro

139 STKPOP 4

140+ LH 3,STKCOUNT

141+ CH 3,=H'0'

142+ BNP NOPOP

143+ SH 3,=H'1'

144+ STH 3,STKCOUNT

145+

146+ LA 2,THESTACK

147+ L

4,0(3,2)

148+NOPOP NOP

148 STKPOP 5

149+ LH 3,STKCOUNT

150+ CH 3,=H'0'

151+ BNP NOPOP

152+ SH 3,=H'1'

153+ STH 3,STKCOUNT

154+

155+ LA 2,THESTACK

156+ L

4,0(3,2)

157+NOPOP NOP

** ASMA043E Previously defined symbol - NOPOP

Avoiding the

Problem: A Correct Solution

Here

is a solution to the problem. It works,

but it complex to write.

The

solution is based on the current location operator, *.

It is a jump to a relative address in bytes.

One has to count carefully.

*STKPOP

MACRO

STKPOP &R

LH 3,STKCOUNT GET THE STACK SIZE

SH 3,=H'1' SUBTRACT 1 TO GET WORD OFFSET

* OF THE TOP ITEM IN

THE STACK

CH 3,=H'0' IS THE NEW SIZE NEGATIVE?

BM

*+20 RX 4 YES, SO CANNOT POP

AN ITEM

STH 3,STKCOUNT RX 4 WORD AND STORE AS NEW SIZE

LA 2,THESTACK RX 4 ADDRESS OF STACK START

L

&R,0(3,2)

RX 4 LOAD ITEM INTO R4

MEND

I

am looking into other solutions, but I don’t think they exist if one is using a

macro. Obviously, this can be done

easily if one uses a subroutine.

Observations

on the Solution

The

complexity of the above instruction is based on the necessity of counting

bytes in the object code, not instructions in the source code.

The

above example is simple, because all instructions to be skipped

have the same length. Let’s look at this

again.

CH 3,=H'0' IS THE NEW SIZE NEGATIVE?

BM

*+20 A type RX instruction, length

4 bytes

STH 3,STKCOUNT This instruction is at address *+4

LA 2,THESTACK This is at address *+12

L

&R,0(3,2)

Another 4-byte instruction at *+16

This address is offset

20 bytes from

that of the BM

instruction.

Given

the expected frequency of branch instructions, even within macros,

there should be an easier way to handle a branch.

In

the next lecture, we discuss that easier way.