Fetch-Execute Cycle

As we shall see, the fetch-execute

cycle forms the basis for operation of a stored-program computer. The CPU fetches each instruction from the

memory unit, then executes that instruction, and fetches the next

instruction. An exception to the “fetch

next instruction” rule comes when the equivalent of a Jump or Go To instruction

is executed, in which case the instruction at the indicated address is fetched

and executed.

Registers vs. Memory

Registers and memory are similar in that both store

data. The difference between the two is

somewhat an artifact of the history of computation, which has become solidified

in all current architectures. The basic

difference between devices used as registers and devices used for memory

storage is that registers are usually faster and more expensive (see below for

a discussion of registers and Level–1 Cache).

The origin of the register vs. memory distinction can be

traced to two computers, each of which was built in the 1940’s: the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator – becoming operational in 1945) and the EDSAC (Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator – becoming operational in 1949). Each of the two computers could have been

built with registers and memory implemented with vacuum tubes – a technology

current and well-understood in the 1940’s.

The difficulty is that such a design would require a very large number

of vacuum tubes, with the associated cost and reliability problems. The ENIAC solution was to use vacuum tubes in

design of the registers (each of which required 550 vacuum tubes) and not to

have a memory at all. The EDSAC solution

was to use vacuum tubes in the design of the registers and mercury delay lines

for the memory unit.

In each of the designs above, the goal was the same – to

reduce the number of “storage units” that required the expensive and

hard-to-maintain vacuum tubes. This

small number of storage units became the register file associated with the

central processing unit (CPU). It was

not until the MIT Whirlwind in 1952 that magnetic core memory was introduced.

In modern computers, the CPU is usually implemented on a

single chip. Within this context, the

difference between registers and memory is that the registers are on the CPU

chip while most memory is on a different chip.

Now that L1 (level 1) caches are appearing on CPU chips (all Pentium™

computers have a 32 KB L1 cache), the main difference between the two is the

method used by the assembly language to access each. Memory is accessed by address as if it were

in the main memory that is not on the chip and the memory management unit will

map the access to the cache memory as appropriate. Register memory is accessed directly by

specific instructions. One of the

current issues in computer design is dividing the CPU chip space between

registers and L1 cache: do we have more registers or more L1 cache? The current answer is that it does not seem

to make a difference.

Both memory and registers can be viewed as collections of D flip-flops, as discussed in a

previous chapter. The main difference is

that registers (as static memory) may

actually be built from these flip-flops, while computer memory is fabricated

from a different technology called dynamic

memory. We often describe main

memory as if it were fabricated from flip-flops as this leads to a model that

is logically correct.

A flip-flop stores one bit of data. An N–bit register is a collection of N

flip-flops; thus a

32–bit register is built from 32 flip-flops.

The CPU contains two types of registers, called special purpose registers and general

purpose registers. The general

purpose registers contain data used in computations and can be accessed

directly by the computer program. The

special purpose registers are used by the control unit to hold temporary

results, access memory, and sequence the program execution. Normally, with one now-obsolete exception,

these registers cannot be accessed by the program.

The program status

register (PSR), also called the program

status word (PSW), is one of the

special purpose registers found on most computers. The PSR contains a number of bits to reflect

the state of the CPU as well as the result of the most recent computation. Some of the common bits are

C the carry-out

from the last arithmetic computation

V Set to 1 if the last arithmetic operation resulted in an overflow

N Set to 1 if the last arithmetic operation resulted in a negative number

Z Set to 1 if the last arithmetic operation resulted in a zero

I Interrupts enabled

(Interrupts are discussed later)

More on the CPU (Central Processing Unit)

The central processing unit

contains four major elements

1) The

ALU (Arithmetic Logic Unit), and

2) The

control unit, and

3) The

register file (including user registers and special-purpose registers), and

4) A

set of buses used for communications within the CPU.

The next figure shows a

better top-level view of the CPU, showing three data buses and an ALU optimized

for standard arithmetic. Most arithmetic

(consider addition: C = A + B) is based on production of a result from two

arguments. To facilitate such

operations, the ALU is designed with two inputs and a single output. As each input and output must be connected to

a bus internal to the CPU, this dictates at least three internal CPU buses.

The register file

contains a number of general-purpose registers accessible to the assembly

language operations (often numbered 0 through some positive integer) and a

number of special-purpose registers not directly accessed by the program. With numbered registers (say R0 through R7)

it is often convenient to have R0 be identically 0. Such a constant register greatly simplifies

the construction of the control unit.

Some of the special purpose

registers used by the central processing unit are listed next.

PC the program counter contains the address of

the assembly language instruction

to be executed next.

IR the instruction register contains the

binary word corresponding to the machine

language version of the

instruction currently being executed.

MAR the memory address register contains the

address of the word in main memory

that is being

accessed. The word being addressed

contains either data or

a machine language

instruction to be executed.

MBR the memory buffer register (also called MDR

for memory data register) is the

register used to

communicate data to and from the memory.

We may now sketch some of

the operation of a typical stored program computer.

Reading Memory First

place an address in the MAR.

Assert

a READ control signal to command memory to be read.

Wait

for memory to produce the result.

Copy

the contents of the MBR to a register in the CPU.

Writing Memory First

place and address in the MAR

Copy

the contents of a register in the CPU to the MBR.

Assert

a WRITE control signal to command the memory.

We have mentioned the

fetch-execute cycle that is common to all stored program computers. We may now sketch the operation of that cycle

Copy the contents of the PC into the MAR.

Assert a READ control

signal to the memory.

While waiting on the

memory, increment the PC to point to the next instruction

Copy the MBR into the

IR.

Decode the bits found

in the IR to determine what the instruction says to do.

The control unit

issues control signals that cause

the CPU (and other components of the computer) to fetch the instruction to the

IR (Instruction Register) and then execute the actions dictated by the machine

language instruction that has been stored there. One might imagine the following sequence of

control signals corresponding to the instruction fetch.

T0: PC to Bus1,

Transfer Bus1 to Bus3, Bus3 to MAR, READ.

T1: PC

to Bus1, +1 to Bus2, Add, Bus3 to PC.

T2: MBR

to Bus2, Transfer Bus2 to Bus3, Bus3 to IR.

This simple sequence

introduces a number of concepts that will be used later.

1. The

internal buses of the CPU are named Bus1, Bus2, and Bus3.

2. All

registers can transfer data to either Bus1 or Bus2.

3. Only

Bus3 can transfer data into a register.

4. Only

the ALU can transfer data from either Bus1 to Bus3 or Bus2 to Bus3.

It does this by a specific

transfer operation.

5. Control

signals are named for the action that they cause to take place.

Operation of the

Control Unit

We now examine very briefly the two most common methods for

building a control unit. Recall that the

only function of the control unit is to emit control signals, so that the

design of a control unit is just an investigation of how to generate control

signals. There are two major classes of

control units: hardwired and microprogrammed (or microcoded). In order to see the difference, let’s write

the above control signals for the common fetch sequence in a more compact

notation.

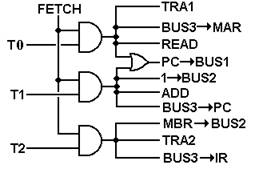

T0: PC ® Bus1, TRA1, Bus3 ® MAR,

READ.

T1: PC

®

Bus1, +1 ®

Bus2, ADD, Bus3 ®

PC.

T2: MBR

®

Bus2, TRA2, Bus3 ®

IR.

Here we have used ten

control signals. Remember that the ALU

has two inputs, one from Bus1, one from Bus2, and outputs its results on

Bus3. The control signals used are:

PC ®

Bus1 Copy the contents of the PC

(Program Counter) onto Bus1

+1 ® Bus2 Copy the contents of the constant

register +1 onto Bus2.

MBR ® Bus2 Copy the contents of the MBR (Memory

Buffer Register) onto Bus2

TRA1 Causes

the ALU to copy the contents of Bus1 onto Bus3

TRA2 Causes

the ALU to copy the contents of Bus2 onto Bus3

ADD Causes

the ALU to add the contents of Bus1 and Bus2,

placing

the sum onto Bus3.

READ Causes

the memory to be read and place the results in the MBR

Bus3 ® MAR Copy the contents of Bus3 to the MAR

(Memory Address Register)

Bus3 ® PC Copy the contents of Bus3 to the PC (Program Counter)

Bus3 ® IR Copy the contents of Bus3 to the IR (Instruction Register)

All control units have a

number of important inputs, including the system clock, the IR, the PSR

(program status register) and other status and control signals. A hardwired

control unit uses combinational logic to produce the output. The following shows how the above signals

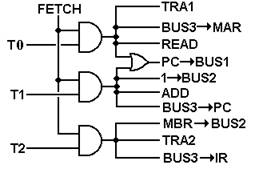

would be generated by a hardwired control unit.

Here we assume that we have the

discrete signal FETCH, which is asserted during the fetch phase of the

instruction processing, and discrete time signals T0, T1, and T2, which would

be generated by a counter within the control unit. Note here that we already have a naming

problem: there will be a distinct phase of the Fetch/Execute cycle called

“FETCH”. During that cycle, the discrete

signal FETCH will be active. This

discrete signal is best viewed as a Boolean value, having only two values:

Logic 1 (+5 volts) and Logic 0 (0 volts).

We next consider how a microprogrammed unit would generate

the above signals. In this discussion,

we shall present a simplified picture of such a control with a number of design

options assumed; these will be explained later in the text.

The central part of a microprogrammed control unit is the micro-memory, which is used to store

the microprogram (or microcode). The microprogram essentially interprets the

machine language instructions in that it causes the correct control signals to

be emitted in the correct sequence. The

microprogram, written in microcode, is stored in a read-only memory (ROM, PROM,

or EPROM), which is often called the control

store.

A microprogrammed control unit functions by reading a

sequence of control words into a microinstruction buffer that is used to

convert the binary bits in the microprogram into control signals for use by the

CPU. To do this, there are several other

components

the mMAR the micro-address of the next control word

to read

the mMBR this holds the last control word read from

the micro-memory

the sequencer this computes the next value of the address

for the mMAR.

The figure below shows the structure of a sample

microprogrammed control unit.

The microprogram for the three steps in fetch would be

10010 00011

11001 01000

00100 10100

The Pipelined CPU

Pipelining is a technique that

allows multiple instructions to be in execution at the same time within the

CPU. Some of the techniques used, such

as instruction pre–fetching, date back to the development of the IBM Stretch

(7030) in the early 1950’s. While it is

possible that most of the theory of pipelining was developed that early, it was

not until the arrival of VLSI chips with their excess of transistors that

pipelining really became effective.

While the design is called

“pipelining”, it really ought to be called “assembly lining”, because an

instruction pipeline resembles nothing so much as the assembly line in an

automobile plant. At each stage in an

automobile assembly line, a distinct operation is performed on the car

assembly, leading at the end to a complete automobile. In a CPU pipeline, the execution of an

instruction is broken into primitive steps that are assigned to independent

units.

The Assembly Line

Here is a picture of the Ford

assembly line in 1913. It is the number

of cars per hour that roll off the assembly line that is important, not the

amount of time taken to produce any one car.

Henry Ford began working on the

assembly line concept about 1908 and had essentially

perfected the idea by 1913. His

motivations are worth study. In earlier

years, automobile manufacture had been done by highly skilled technicians, each

of whom assembled the whole car. It

occurred to Mr. Ford that he could get more get more workers if he did not

require such a high skill level. One way

to do this was to have each worker perform only a small

number of tasks related to manufacture of the entire automobile. It soon became obvious that is was easier to

bring the automobile to the worker than have the worker (and

his tools) move to the automobile. The CPU pipeline has a number of

similarities.

1. The execution of an instruction is

broken into a number of simple steps, each

of which can be

handled by an efficient execution unit.

2. The CPU is designed so that it can

simultaneously be executing a number of

instructions, each

in its own distinct phase of execution.

3. The important number is the number of

instructions completed per unit time,

or equivalently

the instruction issue rate.

The MIPS Pipeline

The best way to discuss the

pipeline idea is to show a sample high–level diagram. This is the pipeline for the MIPS (Microprocessor without Interlocked Pipeline Stages [R105])

that was developed in 1981 by a team at Stanford

University lead by John L. Hennessy. Our

description of the CPU for the MIPS comes from the standard text by Patterson

and Hennessy [R80]; the second author was the one who lead the development team.

The MIPS pipeline design is based on

the five–step instruction execution discussed; the pipeline will have five

stages, with one stage for each step in the execution of a typical instruction.

1. IF: Fetch instruction from memory.

2. ID: Decode the instruction and read two

registers.

3. EX: Execute the operation or calculate an

address.

4. MEM: Access an operand in data memory or write

back a result.

5. WB:

For LW (load word) only, write the results of the memory read into a register.

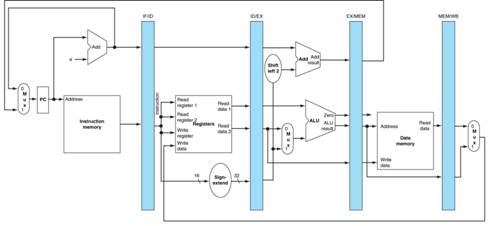

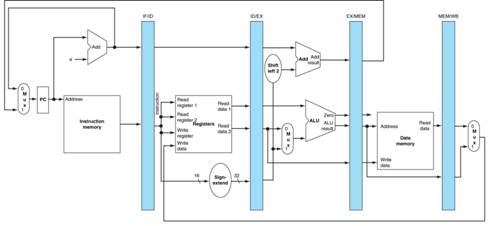

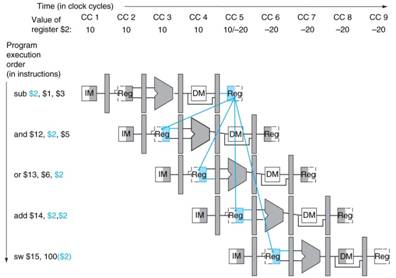

Here is a figure, taken from

[R80] to illustrate the MIPS pipeline.

It shows the execution pipeline broken into five stages, with additional

register sets inserted between the stages.

Thus, we have the IF/ID (Instruction Fetch / Instruction Decode)

register set between the first two stages.

Note also, the three ALUs; two extra are required to support pipelining. One should consider the instructions as

moving from left to right in this pipeline; those to the right are in a more

advanced stage of execution.

A fuller

explanation of this figure will be given in the graduate course on computer

architecture. The only reason for

showing it here is to make two points.

1. The

execution of an instruction can be broken into sequential stages.

2. There

is additional hardware required to support pipelining.

As a design

feature, pipelining is similar to very many enhancements. If added “after the fact”, it will be very

hard to implement correctly. It is much

better to design the ISA (Instruction Set Architecture) with pipelining in

mind. This brings home a very important feature of design: the

compilers, operating system, ISA, and hardware implementation must all be

designed at the same time. Put another

way, the system must be designed as a whole, with appropriate trade–offs

between subsystems in order to optimize the overall performance.

Features of

the MIPS design that were intended to facilitate pipelining include:

1. The

fact that all instructions are the same length.

2. The

small number of instruction formats.

3. The

regularity of the instruction format, always beginning with a 6–bit opcode,

followed by two 5–bit register

identifiers.

4. The

use of the load/store design, restricting memory accesses to

only two, well defined, steps.

5. The

fact that only one instruction writes to memory and that as the last stage in

instruction execution. This has major impact on the design to handle

interrupts,

especially the page–fault

interrupts generated by a virtual memory system.

Many of these

features are precisely those that characterize a RISC design, as discussed

later in this chapter. In fact, the MIPS

is properly called a RISC architecture. The reader is advised to consult with the

referenced textbook [R80] for more details on this design.

In order to

discuss the operation of the pipeline and focus on the difficulties associated

with a correct pipeline design, we focus on a five–line fragment of MIPS

assembly language.

SUB $2, $1, $3 # The “$” denotes a register.

$2

AND $12, $2, $5 # is

register 2 in the register file.

OR $13, $6, $2 # Note that

$2 is used in each line.

ADD $14, $2, $2 # 100($2) is an address calculation.

SW $15,

100($2) # Add 100 to contents of $2.

Ideally a

pipelined CPU should function in much the same way as an automobile assembly

line; each stage operates in complete independence of every other stage. The instruction is issued and enters the pipeline.

It then moves through each of the execution stages, until it is

completed and exits the pipeline. The

next table shows the stage of execution for each of the five instructions above

for each clock cycle. In clock cycle 5,

the SUB instruction is in WB, the AND instruction is in MEM, etc.

|

Time (Clock Cyles)

|

CC1

|

CC2

|

CC3

|

CC4

|

CC5

|

CC6

|

CC7

|

CC8

|

CC9

|

|

SUB $2, $1, $3

|

IF

|

ID

|

EX

|

MEM

|

WB

|

|

|

|

|

|

AND $12, $2, $5

|

|

IF

|

ID

|

EX

|

MEM

|

WB

|

|

|

|

|

OR $13, $6, $2

|

|

|

IF

|

ID

|

EX

|

MEM

|

WB

|

|

|

|

ADD $14, $2, $2

|

|

|

|

IF

|

ID

|

EX

|

MEM

|

WB

|

|

|

SW $15, 100($2)

|

|

|

|

|

IF

|

ID

|

EX

|

MEM

|

WB

|

Another way to look at this is ordered by

clock pulse and shows what four of the five stages in the pipeline is doing at any given time.

WB is omitted to keep the table readable.

|

CC

|

IF

|

ID

|

EX

|

MEM

|

|

1

|

SUB $2, $1, $3

|

An

earlier instruction.

|

An

earlier instruction.

|

An

earlier instruction.

|

|

2

|

AND $12, $2, $5

|

SUB $2, $1, $3

|

An

earlier instruction.

|

An

earlier instruction.

|

|

3

|

OR $13, $6, $2

|

AND $12, $2, $5

|

SUB $2, $1, $3

|

An

earlier instruction.

|

|

4

|

ADD $14, $2, $2

|

OR $13, $6, $2

|

AND $12, $2, $5

|

SUB $2, $1, $3

|

|

5

|

SW $15, 100($2)

|

ADD $14, $2, $2

|

OR $13, $6, $2

|

AND $12, $2, $5

|

We can use either of these two tables to

examine the progression of instructions through the execution pipeline. Ideally, as an instruction progresses through

the pipeline it does not depend on the results of any other instruction now in

the pipeline. Obviously, this cannot

always be the case; in our example above, it is not the case.

There is one absolute requirement for

correct operation of a pipeline. We use

the above code fragment to illustrate this requirement.

SUB $2, $1, $3

AND $12, $2, $5

OR $13, $6, $2

ADD $14, $2, $2

SW $15,

100($2)

The effect of executing this code must be

the same as it would have been had the code been executed on a simple

non–pipelined CPU. In particular, the

value in register $2, computed in the first instruction, must be the value used

in all following instructions. Suppose

that the effect of the SUB instruction is to change the

value stored in $2 from 10 to –20. The

next four instructions must use this new value, not the older value of +10.

What can we

say that will always be true about pipelined execution?

1. It

is not possible for any instruction to depend on the results of instructions

that will execute in the

future. This is a logical impossibility.

2. Instructions

can have dependence only on those previously executed; however,

there are no issues associated

with dependence on instructions that have completed

execution and exited the

pipeline. Results of these instructions

have been stored in

either the memory or register

file, and are available for immediate use.

3. It

is possible, and practical, to design a compiler that will minimize problems in

the pipeline. This is a desirable result of the joint

design of compiler and ISA.

4. It

is not possible for the compiler to eliminate all pipelining problems without

reducing the CPU to a non–pipelined

datapath, which is unacceptably slow.

A pipeline hazard occurs when an

instruction cannot complete a step in its execution, due to some event in the

previous clock cycle. When an

instruction must be held for one or more clock pulses in order to complete a

step in its execution, this is called a “pipeline

stall”, informally a “bubble”. These pipeline problems are called

hazards. They come in three varieties: structural

hazards, data hazards, and control hazards.

Structural hazards occur when

the instruction set architecture does not match the design of the control

unit. In other words, the hardware

cannot support the combination of instructions that we want to execute in the

same clock cycle. Careful design can

eliminate this type of problem.

Data hazards are due to tight

dependencies in sequences of machine language instructions. These occur when one step in the pipeline

must await the completion of a previous instruction. A good compiler can reduce these hazards, but

not eliminate them. Our example code

section above illustrates a typical data hazard.

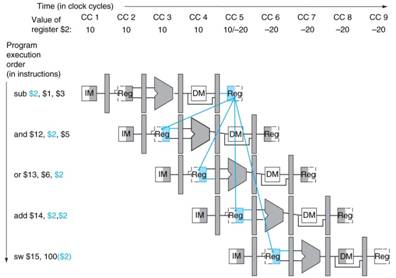

The next

figure, taken from [R80] assumes that the effect of the first instruction is to

change the contents of register $2 from 10 to –20. This result is not available in the register

file until the first half of CC 5; thus the two instructions (AND, OR)

following the first get bad values.

Control hazards, also called branch hazards, arise from the need to

make a decision based on the results of one instruction while others are executing. A typical example would be the execution of a

conditional branch instruction. If the

branch is taken, the instructions currently in the pipeline might be invalid. As an example, consider the following

execution flow which has no data hazards.

The instruction at address 40 is in

the Execution stage of the datapath,

The

instruction at address 44 is in the Instruction Decode stage, and

The instruction at address 48 is in

the Instruction Fetch stage.

The MIPS is a byte–addressable machine,

with 32–bit instructions. The address of

the instruction after that at 40 is 44. When the BEQ executes, the PC already has

value 44. The branch target address is

the value 7 multiplied by 4 and added to the PC; 4·7 + 44 = 72.

40 BEQ $1, $3, 7 #

Branch if ($1 == $3)

44 AND $12, $2, $5

48 OR $13, $6, $2

52 ADD $14,

$2, $2

72 LW $4,

50($7)

There are two possible outcomes

for the execution of the BEQ:

1. The branch is not

taken. Execution proceeds without delay.

2. The

branch is taken. The partially executed

instructions at addresses 44 and 48 must

be removed from the pipeline

without having changed the machine state.

A more

thorough discussion of pipelining, pipeline hazards, and the remedies to those

hazards would be interesting but take too much time. This textbook requires a

knowledge of what a data hazard is, because they are considered in the

design of some supercomputers.

Levels of Machines and Virtual Machines

As with any system, a

computer can be viewed from a number of perspectives or levels of detail. Each level corresponds to a virtual machine –

one able to execute directly a specific language. For example, many people view computers as

virtual machines that directly execute e-mail programs, spread sheets, or word

processors. These people do not care

about the lower level instructions that actually cause the machine to function,

nor should they.

Put another way, many people

consider the computer as just another appliance – that is, something that does

its job with little human interaction.

In this author’s opinion, this fact is one of the major achievements of

the computer industry.

“Levels” of Automobiles

In order to motivate the

idea of levels of machines, let us consider what might be called “levels of

automobiles” or more precisely, the level of detail at which a particular user

chooses to understand an automobile. As

an example, let us think about the Rolls Royce Phantom (the 2004 model is

priced at only $470,000, in case you want to buy one). There are a number of levels at which to view

this automobile.

The automobile collector will view the car as a work of art. The possibility that one might drive the

thing might not even occur to him or her.

The VIP (very rich person or diplomat) will view the automobile as

something that transports him or her to the desired destination. Admittedly, the automobile does not drive

itself, but it might as well, given the fact that it almost always has a paid chauffeur.

The casual driver will understand the basics of operating the vehicle –

use of the keys, transmission, steering wheel, and other controls. To this person, the automobile is just a

machine that can be controlled in predictable ways.

The more involved driver will, in addition,

understand that the automobile comprises a number of subsystems, such as the

chassis, engine, transmission, and electronic systems. He or she will understand the necessity of

system maintenance without being able to perform it.

The automobile mechanic will understand the details of each of the

automobile subsystems and how to repair them.

Note that this is a lower (more detailed) level of understanding than

the involved driver. The mechanic not

only understands that the subsystems exist but also understands how they work

and how to fix them.

The automobile engineer will understand one of the subsystems in

detail, for example the detailed kinetics of fuel combustion, metallurgy of the

engine block, or dynamics of the electrical system.

Using this analogy, the goal

of this course is to give the student an understanding of a computer somewhere

between that of a mechanic and an engineer.

Levels of Machines in the

Computer Hierarchy

A traditional view of the

computer (see Tanenbaum [R15] or Murdocca

& Heuring [R16]) presents between five and eight

levels of machines. Here we construct a

typical list.

9. Application Programs

(Appliance level),

8. High

Level (Problem Oriented) Languages,

7. Assembly

language,

6. Operating

system services (such as BIOS calls)

5. Binary

machine language,

4. Micro-operation

level (usually microprogramming),

3. Functional

units (memory, ALU, etc.)

2. Logic

gates, including SSI and MSI components.

1. Transistors

and wires.

We skip over level 9 (application

programs) and begin our top-down study with level 8 (High Level

Languages). A high-level language

programmer may experience the computer as a machine that directly executes the

high-level language, such as C++, Visual Basic, COBOL, or FORTRAN. In fact, very few machines are designed for

direct execution of high-level languages (there are several LISP machines and a

FORTH machine), but one may imagine a virtual

machine that does exactly that. In

practice, most virtual machines operating at the high-level language level

achieve their effect by compiling the program into a form suitable for

execution on a lower-level machine. The

figure below shows two of the more common ways in which a high-level language virtual

machine functions.

Before discussing this

figure, it is important to understand the differences between level 6 (the

Operating System/BIOS level) and level 5 (the Binary Machine Language

level). In some aspects, levels 5 and 6

are identical. The major difference is

that level 6 may be regarded as providing standard service routines, such as

those in the Basic Input-Output System (BIOS).

The operating code for both levels 5 and 6 is binary machine code.

Some compilers (mainly the

older ones) compile directly to assembly language, which is then assembled into

calls to level 6 machine language. Some

compile directly to level 6 code.

At this point, we see an

important part of the separation of levels.

Consider modern languages, such as C++ and Java. At level 8, all computers that execute such

code appear to be almost identical, with slight differences (such as integer

sizes) that can be handled by use of macros and other definitions. At level 7, the computers may appear quite

different as each computer brand seems to have its own particular assembly

language.

The transition between

levels 6 and 7 (assembly language & O/S services) and level 5 is often

achieved by a linking loader. This

transition allows programs to be loaded at any free part of memory, rather than

at fixed locations (as was the case with some earlier machines). Thus we have two views of machines – the

level 6/7 virtual machine in which the program always loads at a fixed location

and the level 5 machine in which the program is relocated.

The split between levels 5

and 4 reflects the fact that there are a number of ways in which to implement a

Central Processing Unit (CPU) to execute a machine language. The two primary methods for machine language

execution are hard-wired and microprogrammed.

This separation between these two levels allows a company to build a

series of computers with widely differing performance levels but with the same

assembly/machine language set. For

examples, we look to the IBM 360 series and the DEC (Digital Equipment

Corporation – no longer in business) PDP–11 series.

Here is a quote from an

article by C. Gordon Bell in William Stallings []. It discusses two different implementations of

the IBM 360 family, each with the same assembly language.

“The IBM 360,

introduced in 1964, was one of the earliest computer families to span a range

of price and performance. Along with the

360, IBM introduced the word ‘architecture’ to refer to the various processing

characteristics of a machine as seen by the programmer and his programs. In the initial 360 product family, the model

91 exceeded the model 20 in performance by a factor of 300, in memory size by a

factor of 512, and in price by a factor of 100.”

The next three layers form

the basis for the hardware implementation of the computer. As technology improves, we see two trends in

implementation at this level: more powerful units for the same price and

equally powerful units for a lesser price.

One very early example of this was the IBM 709/7090 series, both of

which implemented the same machine language and used the same hardwired control

design. The difference is that the IBM

709 used vacuum tubes as the basic circuit elements, while the IBM 7090 used

transistors.

Probably the major

revolution in computer design occurred at these low levels with the

introduction to the integrated circuit to replace circuits built from discrete

transistors. The transition from

vacuum tubes to transistors resulted in considerable gains in reliability and

reductions in power usage. The

transition from transistors to integrated circuits, especially VLSI (Very Large

Scale Integration) chips allowed the introduction of the modern micro-computer

and all that has gone with it.

RISC vs. CISC Computers

One of the recent developments in computer architecture is

called by the acronym RISC. Under this

classification, a design is either RISC or CISC, with the following

definitions.

RISC Reduced Instruction

Set Computer

CISC Complex Instruction Set Computer.

The definition of CISC architecture is very simple – it is

any design that does not implement RISC architecture. We now define RISC architecture and give some

history of its evolution.

The source for these notes is the book Computer Systems

Design and Architecture, by Vincent P. Heuring

and Harry F. Jordan [R03].

One should note that while the name “RISC” is of fairly

recent origin (dating to the late 1970’s) the concept can be traced to the work

of Seymour Cray, then of Control Data Corporation, on the CDC–6600 and related machines. Mr. Cray did not think in terms of a reduced

instruction set, but in terms of a very fast computer with a well-defined

purpose – to solve complex mathematical simulations. The resulting design supported only two basic

data types (integers and real numbers) and had a very simple, but powerful,

instruction set. Looking back at the

design of this computer, we see that the CDC–6600 could have been called a RISC

design.

As we shall see just below, the entire RISC vs. CISC

evolution is driven by the desire to obtain maximum performance from a computer

at a reasonable price. Mr. Cray’s

machines maximized performance by limiting the domain of the problems they

would solve.

The general characteristic of a CISC architecture is the

emphasis on doing more with each instruction.

This may involve complex instructions and complex addressing modes; for

example the MC68020 processor supports 25 addressing modes.

The ability to do more with each instruction allows more

operations to be compressed into the same program size, something very

desirable if memory costs are high. Some

historical data will illustrate the memory issue. Better cost data are found in the chapter on

memory.

|

Time

|

Cost of memory

|

Cost of disk drive

|

|

Introduction of MC6800

|

$500 for 16KB RAM

|

$55,000 for 40 MB

|

|

Introduction of MC68000

|

$200 for 64 KB RAM

|

$5,000 for 10 MB

|

|

Now (Micron 4/10/2002)

|

$49 for 128 MB RAM

|

$149 for 20 GB

|

Another justification for the CISC architectures was the

“semantic gap”, the difference between the structure of the assembly language

and the structure of the high level languages (COBOL, C++, Visual Basic,

FORTRAN, etc.) that we want the computer to support. It was expected that a more complicated

instruction set (more complicated assembly language) would more closely

resemble the high level language to be supported and thus facilitate the

creation of a compiler for the assembly language.

One of the first motivations for the RISC architecture came

from a careful study of the implications of the semantic gap. Experimental studies conducted in 1971 by

Donald Knuth and 1982 by David Patterson showed that nearly 85% of a programs

statements were simple assignment, conditional, or procedure calls. None of these required a complicated

instruction set. It was further notes

that typical compilers translated complex high level language constructs into

simpler assembly language statements, not the complicated assembly language

instructions that seemed more likely to be used.

The results of this study are quoted from an IEEE Tutorial

on RISC architecture [R05]. This table

shows the percentages of program statements that fall into five broad

classifications.

|

Language

|

Pascal

|

FORTRAN

|

Pascal

|

C

|

SAL

|

|

Workload

|

Scientific

|

Student

|

System

|

System

|

System

|

|

Assignment

|

74

|

67

|

45

|

38

|

42

|

|

Loop

|

4

|

3

|

5

|

3

|

4

|

|

Call

|

1

|

3

|

15

|

12

|

12

|

|

If

|

20

|

11

|

29

|

43

|

36

|

|

GOTO

|

2

|

9

|

--

|

3

|

--

|

|

Other

|

|

7

|

6

|

1

|

6

|

The authors of this study made the following comments on the

results.

“There is quite good

agreement in the results of this mixture of languages and applications. Assignment statements predominate, suggesting

that the simple movement of data is of high importance. There is also a preponderance of conditional

statements (If, Loop). These statements are implemented in machine

language with some sort of compare and branch instruction. This suggests that the sequence control

mechanism is important.”

The “bottom line” for the

above results can be summarized as follows.

1) As

time progresses, more and more programs will be written in a compiled high-

level language, with much

fewer written directly in assembly language.

2) The

compilers for these languages do not make use of the complex instruction

sets provided by the architecture

in an attempt to close the semantic gap.

In 1979, the author of these

notes attended a lecture by a senior design engineer from IBM. He was discussing a feature of an

architecture that he designed: he had put about 6 months of highly skilled labor

into implementing a particular assembly language instruction and then found

that it was used less than 1/10,000 of a percent of the time by any compiler.

So the “semantic gap” – the

desire to provide a robust architecture for support of high-level language

programming turned out to lead to a waste of time and resources. Were there any other justifications for the

CISC design philosophy?

The other motivation for the RISC architecture is that a

complex instruction set implies a slower computer. It is not just the fact that the more complex

instructions execute more slowly than the simpler instructions. There is also the fact that making a CPU

capable of handling more complex instructions causes it to execute simple

instructions more slowly.

Thus we are facing the facts that the more complex

instruction sets are not necessary and that dropping the ability to support

them will yield a faster CPU. There are

other factors that favor the RISC architecture, specifically the fact that

speed-up techniques such as instruction pre-fetching and instruction pipelining

are more easily achieved for simple instructions.

The name RISC, Reduced

Instruction Set Computer, focuses on reducing the number and complexity of

instructions in the machine. A number of

common strategies are:

1) Fixed instruction

length, generally one word. This

simplifies instruction fetch.

2) Simplified

addressing modes.

3) Fewer

and simpler instructions in the instruction set.

4) Only

load and store instructions access memory; no add memory to register, etc.

5) Let

the compiler do it. Use a good compiler

to break complex high-level language

statements into a number of

simple assembly language statements.

The philosophy behind the RISC

approach is well described in the IEEE tutorial. Here we pick up on a narrative by a design

engineer who worked on the IBM 801 project.

“About this point,

several people, including those who had been working on microprogramming tools,

began to rethink the architectural design principles of the 1970’s. In trying to close the ‘semantic gap’, these

principles had actually introduced a ’performance gap’. The attempt to bridge the gap with WCS’s

[Writable Control Stores – microprogrammed control units] was unsuccessful.”

“A new computer

design philosophy evolved: Optimizing compilers could be used to compile

‘normal’ programming languages down to instructions that were as unencumbered

as microinstructions in a large virtual address space, and to make the

instruction cycle time as fast as the technology would allow. These machines would have fewer instructions

– a reduced set – and the remaining instructions would be simple and would

generally execute in one cycle – reduced instructions – hence the name reduced

instruction set computers (RISC’s).

RISC’s inaugurated a new set of architectural design principles.

1. Functions should be kept

simple unless there is a very good reason to do

otherwise.

2. Microinstructions should not

be faster than simple instructions.

3. Microcode is not magic.

4. Simple decoding and

pipelined execution are more important than

program size.

5. Compiler technology should

be used to simplify instructions rather

than to generate complex

instructions.”

The narrative from the tutorial

continues with remarks on the RISC architectures developed at the University of California

at Berkeley.

“Although each

project [the Berkeley RISC I and RISC II and the IBM 801] had different

constraints and goals, the machines they eventually created have a great deal

in common.

1. Operations are

register-to-register, with only LOAD and STORE

accessing memory.

2. The operations and

addressing modes are reduced. Operations

between registers complete in one cycle, permitting a simpler, hardwired

control for each RISC, instead of microcode.

Multiple-cycle instructions such as floating-point arithmetic are either

executed in software or in a special-purpose processor. (Without a coprocessor, RISC’s have mediocre

floating-point performance.) Only two

simple addressing modes, indexed and PC-relative, are provided. More complicated addressing modes can be

synthesized from the simple ones.

3. Instruction formats are

simple and do not cross word boundaries.

This restriction allows RISC’s to remove instruction decoding time from

the critical execution path. … RISC

register operands are always in the same place in the

32-bit word, so register access can take place simultaneously with opcode

decoding. This removes the instruction

decoding stage from the pipelined execution, making it more effective by

shortening the pipeline.”

There are a number of other

advantages to the RISC architecture. We

list a few

Better Access to Memory

According to the IEEE Tutorial

“Register-oriented

architectures have significantly

lower data memory bandwidth. Lower data

memory bandwidth is highly desirable since data access is less predictable than

instruction access and can cause more performance problems.”

We note that, even at 6.4

GB/second data transfer rates, access to memory is still a bottleneck in modern

computer design, so any design that reduces the requirement for memory access

(here called reducing the memory bandwidth) would be advantageous.

Better Support of Compilers

According to the IEEE Tutorial

“The load/store

nature of these [existing RISC] architectures is very suitable for effective

register allocation by the compiler; furthermore, each eliminated memory

reference results in saving an entire instruction.”

We note here that more

effective register allocation by a compiler will usually result in

faster-running code. We see this as

another advantage of the RISC design.

The Dynamic–Static Interface

In order to understand the DSI, we must place

it within the context of a compiler for a higher–level language. Although most compilers do not emit assembly

language, we shall find it easier to under the DSI if we pretend that they do.

What does the compiler output?

There are two options:

1. A very simple assembly language.

This requires a sophisticated compiler.

2. A more complex assembly language. This may allow a simpler compiler,

but it requires a more complex

control unit.

The DSI really defines the division between

what the compiler does and what the microarchitecture does. The more complexity assigned to the compiler,

the less that is assigned to the control unit, which can be simpler, faster,

and smaller.

One should put the DSI conversation within

the context of the fact that we have become very good at writing efficient

compilers. This is especially true in

management of the register file, as well as identifying code segments that can

be run in parallel, were parallel execution units available. Some modern hardware architectures explicitly

allow multiple instructions to be issued at once, but depend on the compiler to

issue execution packets. While this

grouping of instructions into execution packets could be done by hardware at

execution time, that would lead to a great increase in hardware complexity.

Instruction Pre-Fetching

One advantage of the RISC

architecture is seen in the process referred to as

instruction pre-fetching. In this

process, we view the fetch-execute process as a pipeline.

In a traditional fetch-execute

machine, the instruction is first fetched from memory and then executed. Very early in CPU design, it was recognized

that the fetch unit should be doing something during the time interval for

executing the instruction. The logical

thing for the fetch unit to do was to fetch the instruction in the next memory

location on the chance that it would be the instruction that would be executed

next. This process has been shown to

improve computer performance significantly.

The logic to pre-fetch instructions is facilitated by the RISC design

philosophy that all instructions are the same size, so in a machine based on

32-bit words the pre-fetch unit just grabs the next four bytes.

Instruction pre-fetching

appears rather simple, except in the presence of program jumps, such as occur

in the case of conditional branches and the end of program loops. A lot of work has gone into prediction of the

next instruction in such cases, where there are two instructions that could be

executed next depending on some condition.

It may be possible to execute both candidate instructions and discard

the result of the instruction not in the true execution path.

Implications for the Control Unit

The

complex instructions in a CISC computer tend to require more support in the

execution than can conveniently be provided by a hardwired control unit. For this reason, most CISC computers are

microprogrammed to handle the complexity of each of the instructions. For this reason, most CISC instructions

require a number of system clock cycles to execute. The RISC approach emphasizes use of a simpler

instruction set that can easily be supported by a hardwired control unit. As a side effect, most RISC instructions can

be executed in one clock cycle. A given

computer program will compile into more RISC instructions than CISC

instructions, but the CISC instructions execute more slowly than the RISC

instructions. The overall effect on the

computer program may be hard to predict.

According to the tutorial

“Reducing the instruction set further

reduces the work a RISC processor has to do.

Since RISC has fewer types of instructions than CISC, a RISC instruction

requires less processing logic to interpret than a CISC instruction. The effect of such simplification is to speed

up the execution rate for RISC instructions.

In a RISC implementation it is theoretically possible to execute an

instruction each time the computer’s logic clock ticks. In practice the clock rate of a RISC

processor is usually three times that of the instruction rate.”

We close

this section by giving a comparison of some RISC and CISC computers and quoting

some of the experience of the Digital Equipment Corporation when it tried to

manufacture a RISC version of its Micro-VAX (a follow-on

to the PDP-11). Here is the table, taken

from the IEEE tutorial on RISC architecture.

|

|

CISC Type Computers

|

RISC Type

|

|

|

IBM 370/168

|

VAX-11/780

|

Intel 8086

|

RISC I

|

IBM 801

|

|

Developed

|

1973

|

1978

|

1978

|

1981

|

1980

|

|

Instructions

|

208

|

303

|

133

|

31

|

120

|

|

Instruction size (bits)

|

16 – 48

|

16 – 456

|

8 – 32

|

32

|

32

|

|

Addressing Modes

|

4

|

22

|

6

|

3

|

3

|

|

General Registers

|

16

|

16

|

4

|

138

|

32

|

|

Control Memory Size

|

420 Kb

|

480 Kb

|

Not given

|

0

|

0

|

|

Cache Size

|

64 Kb

|

64 Kb

|

Not given

|

0

|

Not given

|

Note the control memory size on the

two RISC type computers – each has no control memory. This implies that the control unit is purely

hardwired. Experience in the 1980’s and

early 1990’s suggested that microprogrammed control units were preferable, even

if they were a bit slower than hardwired units.

It was argued that the speed of the control unit was not the limiting

factor in performance, and it probably was not.

The plain fact, however, was that implementing a hardwired control unit

for some of the complex instruction sets was a daunting challenge not willingly

faced by the computer designers. Rather

than spend a great fortune on designing, building, and debugging such a unit,

they elected to create control units that could be managed – these were

microprogrammed.

With the development of RISC

architecture, hardwired control units again became feasible.

Another Look at Microprogrammed Control Units

In considering the RISC

design, we should recognize the fact that it is not equivalent to use of a

hardwired control unit; only more compatible with such a unit. Many modern control units might be considered

as hybrid, with mostly hardwired control and provisions for the use of

micro-routines (in microcode) to handle useful, but complex, instructions.

It has been hinted above

that microprogramming has been used as a tool to allow feasible and

cost-effective implementations of complex instruction sets. It is profitable to consider the correlation

between complex instructions and the use of a microprogrammed control unit;

specifically asking the question of the allocation of lines of microcode to

assembly language instructions.

Digital

Equipment Corporation (DEC) undertook an experiment to investigate this

correlation and produced a design yielding interesting, but not surprising,

results, which are again quoted from the IEEE tutorial on RISC architecture.

“DEC reported a subsetting

experiment on two implementations of the VAX architecture in VLSI. The VLSI VAX has nine custom VLSI chips and

implements the complete VAX-11 instruction set.

DEC found that 20.0 percent of the instructions are responsible for 60.0

percent of the microcode and yet are only 0.2 percent of all instructions

executed. By trapping to software to

execute these instructions, the MicroVAX 32 was able to fit the subset

architecture onto only one chip, with an optional floating-point processor on

another chip. .. The VLSI VAX uses five

to ten times the resources of the MicroVAX 32 to implement the full instruction

set, yet is only 20 percent faster.”

|

|

VLSI

VAX

|

MicroVAX

32

|

|

VLSI Chips

|

9

|

2

|

|

Microcode

|

480K

|

64K

|

|

Transistors

|

1250K

|

101K

|

The result is obvious – a simple and

cheaper computer will do most of what you want.

The rest can be better done in software.

The RISC/370

This is your authors name for a

hardware / software architecture developed by David A. Patterson [R104]. This experiment focused on the IBM S/360 and

S/370 as targets for a

RISC compiler. One model of interest was

the S/360 model 44. The S/360 model 44

implements only a subset of the S/360 architecture in hardware; the rest of the

functions are implemented in software.

This allows for a simpler and cheaper control unit. The Model 44 was marketed as a low–end S/360,

less powerful and less costly.

A compiler created for the RISC computer

IBM 801 was adapted to emit code for the S/370 treated as a register–to–register

machine, in the style of a RISC computer.

Only a subset of the S/370 instructions was used as a target for the

compiler. Specifically, the type RX

(memory and register) arithmetic instructions were omitted, as were the packed

decimal instructions, all of which are designed to be memory to memory with no

explicit register use.

This subset ran programs 50 percent

faster than the previous best optimizing compiler that used the full S/370

instruction set. Possibly the S/370 was

an overly complex design.

RISC vs. CISC: Final Comments

We give

the final word on the RISC versus CISC controversy to William Stallings [R06],

who ends his chapter on Reduced Instruction Set Computers with these comments.

“The

work that has been done on assessing the merits of the RISC approach can be

grouped into two categories. Quantitative: Attempts to compare

program size and execution speed of programs on RISC and CISC machines that use

comparable technology. Qualitative: Examines issues such as

high–level language support and optimum use of VLSI real estate.”

“Most

of the work on quantitative assessments has been done by those working on RISC

systems … and it has been, by and large, favorable to the RISC approach.”

“There are

several problems with attempting such comparisons.

1. There

is no pair of RISC and CISC machines that are comparable in life–

cycle cost, level of technology,

gate complexity, sophistication of

compiler, operating system

support, and so on.

2. No

definitive test set of programs exists.

Performance varies with the

program.

3. It

is difficult to sort out hardware effects from effects due to skill in

compiler writing.

4. Most

of the comparative analysis of RISC has been done on toy machines

rather than commercial

products. Moreover, most commercially

available

machines advertised as RISC

possess a mixture of RISC and CISC

characteristics. Thus, a fair comparison with a commercial

‘pure play’

CISC machine (e.g., VAX, Pentium)

is difficult.” [R06]